Section 2.4: Product and Quotient Rules

The basic rules will let us tackle simple functions. But what happens if we need the derivative of a combination of these functions?

Example 1

Find the derivative of \( h(x)=\left(4x^3-11\right)(x+3) \)

This function is not a simple sum or difference of polynomials. It’s a product of polynomials. We can simply multiply it out to find its derivative: \[ \begin{align*} h(x)=& \left(4x^3-11\right)(x+3)\\ =& 4x^4-11x+12x^3-33\\ h'(x)=& 16x^3-11+36x^2 \end{align*} \]

Now suppose we wanted to find the derivative of \[f(x)=\left(4x^5+x^3-1.5x^2-11\right)\left(x^7-7.25x^5+120x+3\right)\]

This function is not a simple sum or difference of polynomials. It’s a product of polynomials. We could 'simply' multiply it out to find its derivative as before – who wants to volunteer? Nobody?

We’ll need a rule for finding the derivative of a product so we don’t have to multiply everything out.

It would be great if we can just take the derivatives of the factors and multiply them, but unfortunately that won’t give the right answer. To see that, consider finding derivative of \( h(x)=\left(4x^3-11\right)(x+3) \). We already worked out the derivative, it is \( h'(x)=16x^3-11+36x^2 \). What if we try differentiating the factors and multiplying them? We’d get \( h'(x)=\left(12x^2\right)(1)=12x^2 \), which is radically different from the correct answer.

The rules for finding derivatives of products and quotients are a little complicated, but they save us the much more complicated algebra we might face if we were to try to multiply things out. They also let us deal with products where the factors are not polynomials. We can use these rules, together with the basic rules, to find derivatives of many complicated looking functions.

Derivative Rules: Product and Quotient Rules

In what follows, \(f\) and \(g\) are differentiable functions of \(x\).

Product Rule

\(\frac{d}{dx}\left( f\cdot g \right)=f'\cdot g+f\cdot g'\)

The derivative of the first factor times the second left alone, plus the first left alone times the derivative of the second.

The product rule can extend to a product of several functions; the pattern continues – take the derivative of each factor in turn, multiplied by all the other factors left alone, and add them up: \[\frac{d}{dx}\left( f\cdot g\cdot h \right)=f'\cdot g\cdot h+f\cdot g'\cdot h+f\cdot g\cdot h'\]

Quotient Rule

\[\frac{d}{dx}\left( \frac{f}{g} \right)=\frac{f'\cdot g-f\cdot g'}{g^2}\]

The numerator of the result resembles the product rule, but there is a minus instead of a plus; the minus sign goes with the \(g’\). The denominator is simply the square of the original denominator – no derivatives there.

Example 2

Find the derivative of \( h(x)=\left(4x^3-11\right)(x+3) \)

This is the same function we found the derivative of in Example 1, but let's use the product rule and check to see if we get the same answer. For this first example, we will provide a lot more detail and steps than one usually actually shows when working a problem like this.

Notice we can think of \(h(x)\) as the product of two functions \( f(x)=4x^3-11 \) and \( g(x)=x+3 \). Finding the derivative of each of these, \[ f'(x)=12x^2 \ \text{and}\ g'(x)=1. \]

Using the product rule, \[ \begin{align*} h'(x)=& (f')(g)+(f)(g') \\ =& \left(12x^2\right)(x+3)+\left(4x^3-11\right)(1) \end{align*} \]

To check if this is equivalent to the answer we found in Example 1 we could simplify: \[ \begin{align*} h'(x)=& \left(12x^2\right)(x+3)+\left(4x^3-11\right)(1) \\ =& 12x^3+36x^2+4x^3-11 \\ =& 16x^3+36x^2-11 \end{align*} \]

From this, we can see the answers are equivalent.

Example 3

Find the derivative of \( F(t)=e^t\ln(t) \)

This is a product, so we need to use the product rule. I like to put down empty parentheses to remind myself of the pattern; that way I don’t forget anything: \[F'(t)=(\ )(\ )+(\ )(\ )\]

Then I fill in the parentheses – the first set gets the derivative of , the second gets left alone, the third gets left alone, and the fourth gets the derivative of \[F'(t)=\left(e^t\right)\left(\ln(t)\right)+\left(e^t\right)\left(\frac{1}{t}\right)=e^t\ln(t)+\frac{e^t}{t}.\]

Notice that this was one we could not have done by multiplying out.

Example 4

Find the derivative of \( y=\frac{x^4+4^x}{3+16x^3} \).

This is a quotient, so we need to use the quotient rule. Again, you find it helpful to put down the empty parentheses as a template: \[y'=\frac{(\ )(\ )-(\ )(\ )}{(\ )^2}\]

Then fill in all the pieces: \[y'=\frac{\left(4x^3+\ln(4)\cdot 4^x \right)\left(3+16x^3 \right)-\left(x^4+4^x \right)\left(48x^2 \right)}{\left(3+16x^3 \right)^2}\]

Now for goodness' sake don’t try to simplify that! Remember that simple

depends on what you will do next; in this case, we were asked to find the derivative, and we’ve done that. I expect you to do any basic

simplifications, such as multiplying constants together or doing obvious cancellations or combining of terms, but otherwise please STOP unless there is a reason to simplify further.

Example 5

Suppose a large tank contains 8 kg of a chemical dissolved in 50 liters of water. If a tap is opened and water is added to the tank at a rate of 5 liters per minute, at what rate is the concentration of chemical in the tank changing after 4 minutes?

First we need to set up a model for the concentration of chemical. The concentration would be measured as kg of chemical per liter of water, kg/L. The number of kg of chemical stays constant at 8 kg, but the quantity of water in the tank is increasing by 5 L/min. The total volume of water in the tank after \(t\) minutes is \(50 + 5t\), so the concentration after \(t\) minutes is \[c(t)=\frac{8}{50+5t}.\]

To find the rate at which the concentration is changing, we need the derivative: \[ \begin{align*} c'(t)=& \frac{\frac{d}{dt}(8)\cdot(50+5t)-(8)\cdot\frac{d}{dt}(50+5t)}{(50+5t)^2} \\ =& \frac{(0)\cdot(50+5t)-(8)(5)}{(50+5t)^2} \\ =& -\frac{40}{(50+5t)^2} \end{align*} \]

At \(t = 4\), \[ c'(4)=-\frac{40}{(50+5(4))^2}\approx -0.00816.\]

Note that the units here are kg per liter, per minute, or \( \frac{\text{kg/L}}{\text{min}} \). In other words, this tells us that after 4 minutes, the concentration of chemical is decreasing by 0.00816 kg/L each minute.

More Graphical Interpretations of the Basic Business Math Terms

Returning to our discussion of business and economics topics, in addition to total cost and marginal cost, we often also want to talk about average cost or average revenue.

Recall from the previous section that the Average Cost (AC) for \(q\) items is the total cost divided by \(q\), or \(AC(q)=\frac{TC}{q}\). You can also talk about the average fixed cost, \(\frac{FC}{q}\), or the average variable cost, \(\frac{TVC}{q}\).

Also recall that the Average Revenue (AR) for \(q\) items is the total revenue divided by \(q\), or \(AR(q)=\frac{TR}{q}\). But \(\frac{TR}{q}=\frac{D(q)\cdot q}{q}=D(q)\), so \(AR(q)=D(q)\) (which just the price since \(p=D(q)\)).

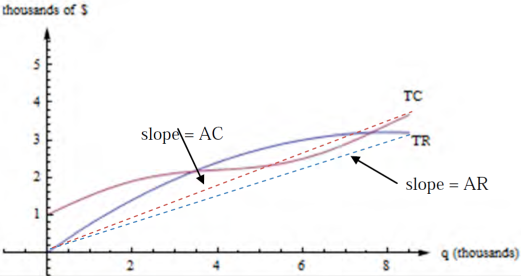

We already know that we can find average rates of change by finding slopes of secant lines. AC, AR, MC, and MR are all rates of change, and we can find them with slopes, too.

\(AC(q)\) is the slope of a diagonal line, from (0, 0) to \((q, TC(q))\).

\(AR(q)\) is the slope of the line from (0, 0) to \((q, TR(q))\), which is the also equal to the price at \((q, TR(q))\) by the calulations in the previous paragraph.

And just as we found marginal Total Cost, we can also find marginal Average Cost.

Example 6

The cost, in thousands of dollars, for producing \(x\) thousand cellphone cases is given by \( C(x)=22+x-0.004x^2 \). Find

- the Fixed Costs,

- the Average Cost when 5 thousand, 10 thousand, or 20 thousand cases are produced,

- the Marginal Average Cost when 5 thousand cases are produced.

- The fixed costs are the costs when no items are produced: \( C(0)=22 \) thousand dollars.

-

The average cost function is total cost divided by number of items, so \[AC(x)=\frac{C(x)}{x}=\frac{22+x-0.004x^2}{x}. \]

Note the units are thousands of dollars per thousands of items, which simplifies to just dollars per item.

At a production of 5 thousand items: \( AC(5)=\frac{22+5-0.004(5)^2}{5}=5.38 \) dollars per item.

At a production of 10 thousand items: \( AC(10)=\frac{22+10-0.004(10)^2}{10}=3.16 \) dollars per item.

At a production of 20 thousand items: \( AC(20)=\frac{22+20-0.004(20)^2}{20}=2.02 \) dollars per item.

Notice that while the total cost increases with production, the average cost per item decreases, because the initial fixed costs are being distributed across more items.

-

For the marginal average cost, we need to find the derivative of the average cost function. We can either calculate this using the quotient rule, or we could use algebra to simplify the equation first (this is the easier option – remember, simplifying before differentiating is almost always easier): \[ \begin{align*} AC(x)=& \frac{22+x-0.004x^2}{x} \\ =& \frac{22}{x}+\frac{x}{x}-\frac{0.004x^2}{x} \\ =& \frac{22}{x}+1-0.004x \\ =& 22x^{-1}+1-0.004x \end{align*} \] (Note: we haven't differentiated yet, only simplified.)

Taking the derivative, \[ AC'(x)=-22x^{-2}-0.004=-\frac{22}{x^2}-0.004.\]

When 5 thousand items are produced, \[ AC'(5)=-\frac{22}{5^2}-0.004=-0.884.\]

Since the units on \(AC\) are dollars per item, and the units on \(x\) are thousands of items, the units on \(AC'\) are dollars per item per thousands of items. This tells us that when 5 thousand items are produced, the average cost per item is decreasing by $0.884 for each additional thousand items produced.